Statistics don’t lie: 33 to 40 percent of the world’s food, that is an estimated $600 billion worth of food, is lost or wasted during or just after harvest every year. This disheartening fact is even more tragic today, while we are facing a looming global food crisis -the war in Ukraine, COVID-19, and climate change have done their part.

At this given moment, we know that one in nine people in the world can’t be fed adequately —that’s more than 800 million suffering from hunger, and the consequences of food loss and waste will only get worse. And if we add up the tremendous waste in natural sources (water) and the CO2 emissions involved in these losses, then we all understand that this is an urgent matter to be addressed.

Why Food loss is even more alarming than food waste

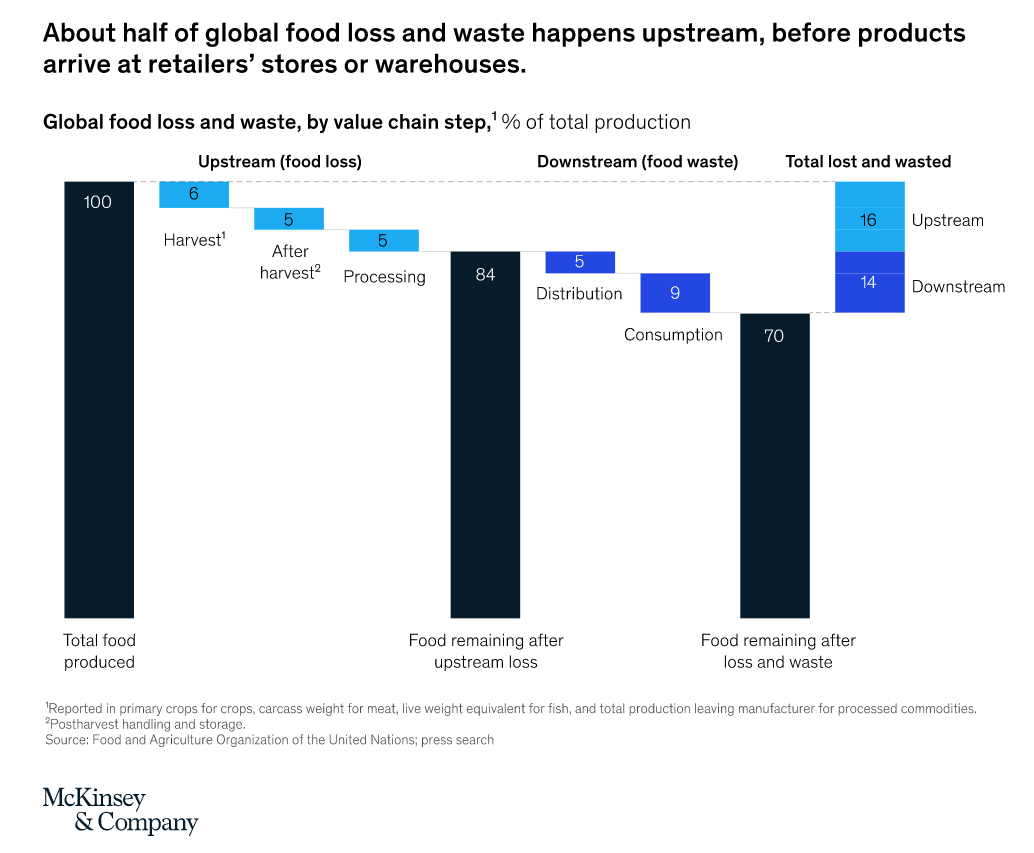

The two terms may seem synonymous, but are not, and the differences are important to understand the root cause of the problem: “food loss” happens at harvest or soon after, that is long before food comes near the consumer, while “food waste” happens after the food reaches the retailer or consumer.

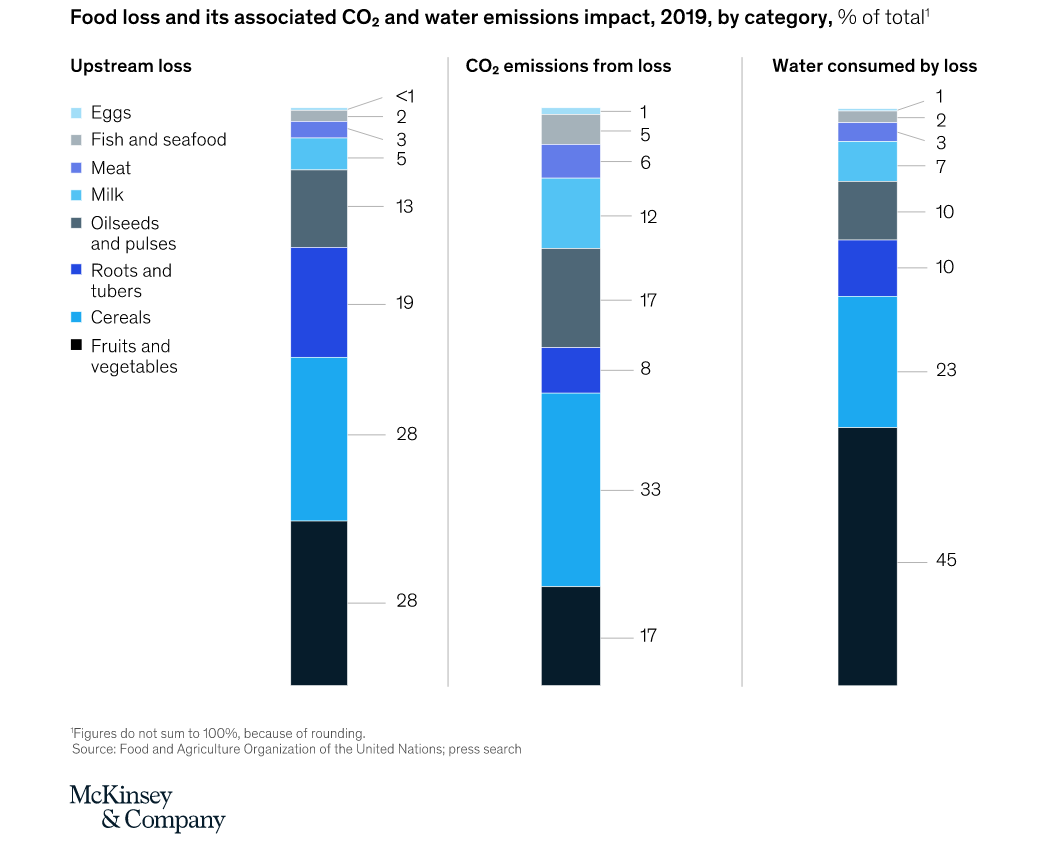

The secondary effects of the loss of the food itself are also alarming: the water consumption linked to food loss and waste amounts to approximately one-fourth of the world’s freshwater supply. Greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions from food loss and waste constitute 8% of the global total, or at least four times those of the aviation industry.

To date, most large-scale efforts to understand and address the problem have focused on food waste, largely because it’s more visible: people see food being wasted in stores, restaurants, and households. But up to half of the food that doesn’t get eaten by humans—worth an estimated $600 billion—is lost at or near the farm, during or just after harvest. Reducing food loss should therefore be treated as a societal and environmental priority.

According to the comprehensive research by McKinsey, there is good news in this case: reducing food loss is immensely achievable. Food manufacturers and retailers, being at the center of the food value chain, are uniquely positioned to lead global efforts to reduce food loss. Researchers believe that they could cut food loss by 50 to 70%. Two-thirds of the food that would otherwise be lost could be redirected to human consumption; the remaining one-third would go to alternative uses, such as bio-based materials or animal feed.

How does food get lost?

According to the research, more than two billion tons of food are lost or wasted every year. About half is lost far before the food reaches the shelves (photo 1).

What is interesting, is that 3 categories we wouldn’t normally think of (fruits and vegetables, cereals, and roots and tubers) account for much of the food loss and the associated CO2 emissions and water use. This is because we usually blame meat and dairy, but these two have a high environmental impact per unit produced (it takes more than 1,000 gallons of water to produce a pound of beef, for example), but in food loss, meat accounts for only about 3%, and dairy for another 5%. (photo 2).

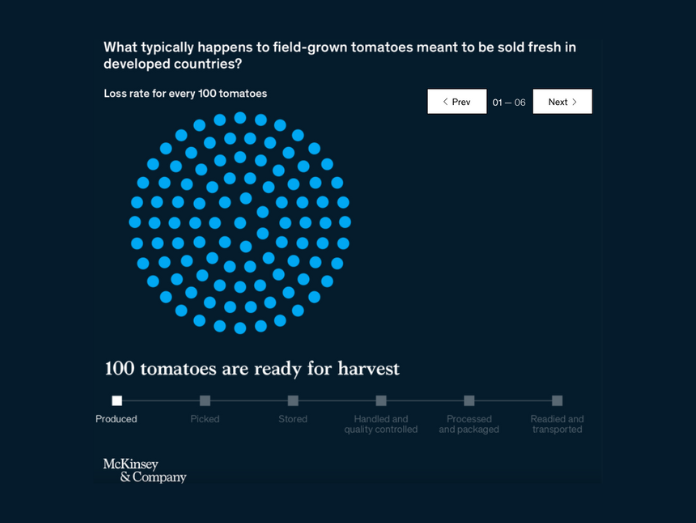

McKinsey’s researchers, in collaboration with the Consumer Goods Forum and its members, and working closely with leading European grocers and distributors, investigated the farm-to-retailer journey, using tomatoes as their test case.

They chose tomatoes because 50 million to 75 million tons of them are lost upstream every year (more than any other fruit or vegetable). In addition, lessons learned from the tomato’s journey can be extrapolated to other fresh-produce categories. Tomatoes are grown and eaten all over the world, are available year-round, can be eaten fresh or go through further processing, must conform to certain standards (color, shape, and so forth), and resemble several other produce categories with regard to perishability.

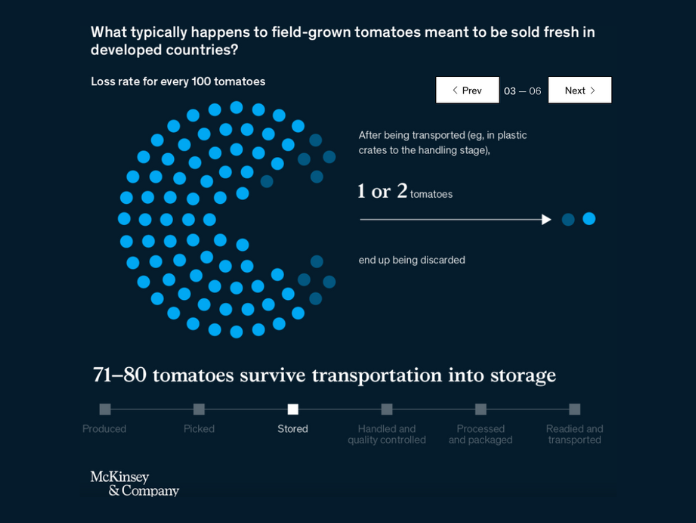

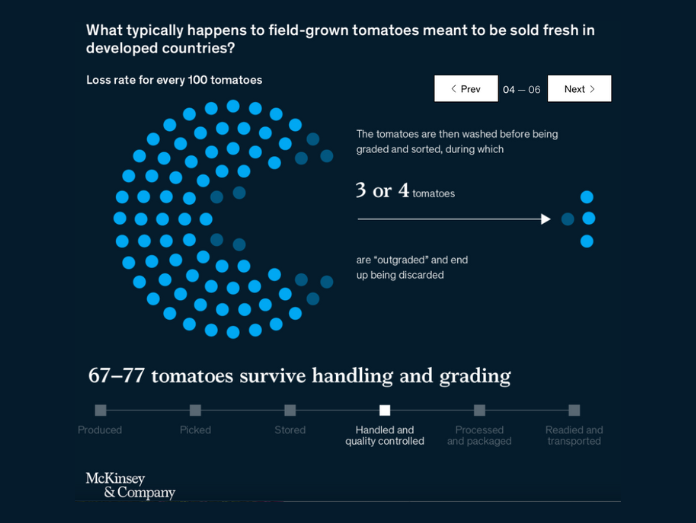

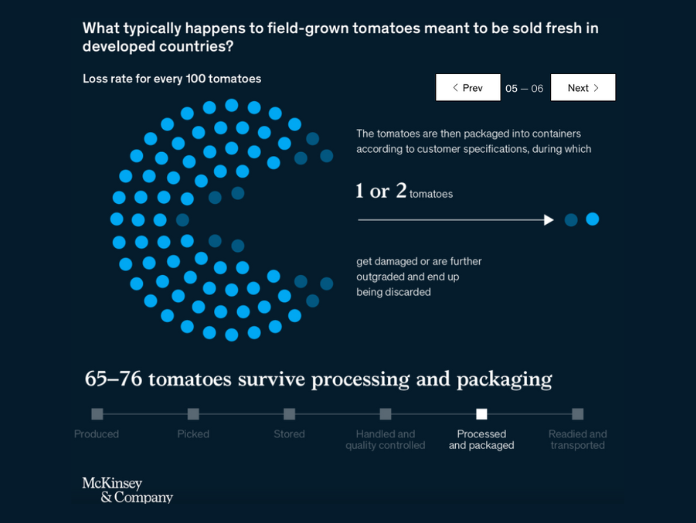

The researchers studied tomato journeys in both developed and developing markets: tomatoes sold fresh and those sent into the processed supply chain, and tomatoes grown in fields as well as in developed-market greenhouses. The following 6-photo scheme illustrates what happens to tomatoes grown in fields in developed markets and sent to retailers to be sold fresh in their stores. As the photos show, in developed countries, out of every 100 tomatoes only 59 to 72 make it to a store shelf. In the developing world, the numbers are grimmer: only 35 to 58 make it to the store.

6 photo-scheme

The research revealed that some food loss results from exogenous factors, such as weather events, or suboptimal practices within a specific stage of the supply chain, such as poor equipment maintenance, but some loss is linked to the interdependencies and interactions among the players in the value chain. Growers may overproduce because they are uncertain about market demand, while manufacturers and retailers often don’t have much transparency into supply. Stringent customer specifications can lead to excessive postharvest outgrading. Most procurement contracts don’t create incentives for reducing food loss.

Solving the food loss problem requires fundamental changes in the ways that stakeholders work together. For tomatoes alone, the potential impact is more than 40 million tons saved every year. Globally, CO2 emissions linked to tomato loss would fall by 60 to 80%. And if this can be done with tomatoes, it can be done with other food categories as well.